Boxer Rebellion

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boxer Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 義和團運動 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 义和团运动 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Righteous Harmony Society Movement | ||||||

|

|||||||

The Boxer Rebellion, also called The Boxer Uprising, by some historians or the Righteous Harmony Society Movement in northern China, was an anti-colonialist, anti-Christian movement by the "Righteous Harmony Society" (Yìhétuán),[1] or "Righteous Fists of Harmony" or "Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists" (known as "Boxers" in English), in China between 1898 and 1901. The uprising took place in response to imperialist expansion involving European opium traders, political invasion, economic manipulation, and missionary evangelism. In 1898 local organizations emerged in Shandong as the result of the imperialist expansion, as well as other internal issues such as the state fiscal crisis and natural disasters. Initially they were suppressed by the Qing Dynasty of China. Later, the Qing Dynasty attempted to expel Foreign influence from China. Under the slogan "扶清灭洋" ("Support the Qing, destroy the foreign"), Boxers across North China attacked mission compounds.

In June 1900 Boxer fighters, lightly armed or unarmed, gathered in Beijing to besiege the foreign embassies. On 21 June the conservative faction of the Imperial Court induced the Empress Dowager Cixi, who ruled in the emperor’s name, to declare war on the foreign powers that had diplomatic representation in Beijing. Diplomats, foreign civilians, soldiers and some Chinese Christians retreated to the Legation Quarter where they stayed for 55 days until the Eight-Nation Alliance brought 20,000 armed troops, to defeat the Boxers.

The Boxer Protocol of 7 September 1901 ended the uprising and provided for severe punishments, including an indemnity of 67-million pounds[2] (450 million taels of silver, to be paid as indemnity over a course of 39 years) to the eight nations involved.

The Qing Dynasty was greatly weakened, and was eventually overthrown, by the 1911 revolution which led to the establishment of the Chinese Republic.

Contents |

Origins of the Boxers

The Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists, known by foreigners as the Boxers, or "I-Ho Magic Boxing", was a secret society founded in the northern coastal province of Shandong.[3] Westerners came to call well-trained, athletic young men "Boxers" due to the martial arts and calisthenics they practiced. Despite the obvious differences between Wushu and European pugilistic boxing, the training for unarmed combat took on the same name to the Europeans.

The Boxers believed that they could, through training, diet, martial arts and prayer, perform extraordinary feats, such as flight, and could become immune to swords and bullets. Further, they popularly claimed that millions of spirit soldiers would descend from the heavens and assist them in purifying China of foreign influences. The Boxers consisted of local farmers/peasants and other workers made desperate by disastrous floods and widespread opium addiction, and found blame in both Christian missionaries, Chinese Christians, and the Europeans colonizing their country. Some Chinese Christians were recent converts and some had been born into the faith- which would suggest that the Christian faith existed in China for at least a generation before the rebellion began, and therefore Christianity was not the sole trigger for the ethnocentric uprising. Missionaries were protected under the policy of extraterritoriality. Aggression toward missionaries and Christians gained the attention of foreign (mainly European) governments.[4]

After the Hundred Days Reform failed, the conservative Empress Dowager Cixi seized power and put the reformist Guangxu Emperor into house arrest. The European powers were sympathetic to the imprisoned emperor, and opposed Cixi's plan to replace the Guangxu emperor. Empress Dowager Cixi decided to use Boxers to expel foreign influences from China; meanwhile, the Boxers would be weakened by foreign forces. Then the Boxer slogan became "support the Qing, destroy the Foreign." (扶清灭洋) [3]

Causes of the Boxer Rebellion

In 1900, the great powers had been chipping away at Chinese sovereignty for sixty years. They had defeated China in several wars and imposed unequal treaties under which foreigners and foreign companies in China were accorded special privileges and immunities from Chinese law. Thus, by 1900, the Qing dynasty that had ruled China for more than two centuries was crumbling and Chinese culture was under assault by powerful alien religious and secular culture.[5]

Several factors contributed to the unrest among Chinese that led to the growth and spread of the Boxer movement. First, a drought, followed by floods, in Shandong province in 1897-1898 forced farmers to flee to cities to seek food. As one observer said, "I am convinced that a few days' heavy rainfall to terminate the long-continued drought...would do more to restore tranquility than any measures which either the Chinese government or foreign governments can take."[6]

Another cause was the land grabs of the Western countries. France, Japan, Russia, and Germany carved out spheres of influence and by 1900 it appeared that China would likely be dismembered with Western powers each ruling a part of the country. The British and Americans wished China to remain intact, while retaining their privileges and treaty ports. The British dominated trade with China, including the important opium trade. Opium addiction was a major problem in China.[7]

A major cause of Chinese discontent was the Christian missionaries, Protestant and Roman Catholic, who came to China in ever increasing numbers. The exemption of missionaries from many laws alienated local Chinese. In 1899, with the help of the French Minister in Beijing, the missionaries obtained an edict granting official rank to each order in the Roman Catholic hierarchy. Local priests, by means of this official status, were able to support their people in legal disputes or family feuds and go over the heads of local officials. After the German government took over territory in Shandong, many Chinese feared that the missionaries, and by extension all Christians, were part of an imperialist attempt to "carve the melon," that is, to divide China and colonize the pieces separately.[8] A Chinese official expressed the brief against the foreigners succinctly, "Take away your missionaries and your opium and you will be welcome."[9]

The growth of the Boxer movement coincided with the Hundred Days Reform (11 June–21 September 1898). Progressive Chinese officials—with support from Protestant missionaries—persuaded the Guangxu Emperor to institute reforms, which alienated many conservative officials by their sweeping nature and led the Empress Dowager to step in and reverse the reforms. The failure of the reform movement disillusioned many educated Chinese, contributing to the weakness of the Qing government.[10][11]

The first conflicts of the Boxer Rebellion were in Shandong province. Suppressed there—and the farmers pacified by timely rains—the shadowy Boxer movement spread northward in early 1900. By late May the thousands of Western and Japanese businessmen, soldiers, and missionaries in Beijing and Tianjin and throughout northern China perceived it as a serious threat to foreign and Christian lives, properties, and privileges.[12]

Commitment of Imperial Army

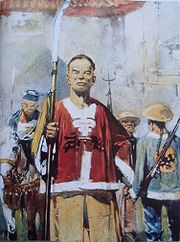

Left: two infantrymen of the New Imperial Army. Front: drum major of the regular army. Seated on the trunk: field artilleryman. Right: Boxers.

Now with a majority of conservatives in the Imperial Court the Empress Dowager changed her long policy of suppressing Boxers; she issued edicts in defense of the Boxers, which drew heated complaints from foreign diplomats in January 1900. In June 1900 the Boxers, now joined by elements of the Imperial army, attacked foreign compounds in the cities of Tianjin and Beijing. The legations of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, the United States, Russia and Japan were all located on the Beijing Legation Quarter close to the Forbidden City in Beijing. The legations were hurriedly linked into a fortified compound that became a refuge for foreign citizens in Beijing. The Spanish and Belgian legations were a few streets away and their staffs were able to arrive safely at the compound. The German legation on the other side of the city was stormed before the staff could escape. When the envoy for the German Empire, Klemens Freiherr von Ketteler, was murdered on 20 June by a Manchurian man, the foreign powers demanded redress. On 21 June Empress Dowager Cixi declared war against all Western powers; regional governors, including Li Hongzhang and Zhang Zhidong, quietly refused to cooperate. Shanghai's Chinese elite supported the provincial governors of southeastern China in resisting the Imperial declaration of war.[13] Later many peasants took up arms and joined the Boxers' cause, but were also defeated.

Imperial Army

Muslim Kansu Braves

A unit of 10,000 Hui Muslims from Gansu under the command of the Chinese Muslim General Dong Fuxiang had been stationed with the rest of the imperial army at Beijing since 1898. They were known as the "Kansu braves".[14] Dong was extremely anti-foreign, and gave full support to Cixi and the boxers. General Dong committed his Muslim troops to join the Boxers to attack the 8 nation alliance. They were put into the rear division, and attacked the legations relentlessly. The westerners called them the "10,000 Islamic rabble".[15][16][17] Casualties suffered by the alliance at the hands of the Muslim troops were so high, that the United States Marine Corps was called in.[18][19] A Japanese chancellor, Sugiyama Akira, and several westerners were shot to death by the Muslim braves.[20][21][22] It was reported that the Muslim troops were going to wipe out the foreigners to return a golden age for China, and the Muslims repeatedly attacked foreign churches, railways, and legations, before hostilities even started.[23] The Muslim troops were armed with modern repeater rifles and artillery, and reportedly enthusiastic about going on the offensive and killing foreigners. Ma Fuxiang led an ambush against the foreigners at Langfang and inflicted many casualties, using a train to escape.

The Muslims terrorized the foreigners who were under siege, and the muslim commander sat on the skin and ate the heart of the German minister von Ketteler.[24]

Another muslim general, Ma Anliang, Tongling of Ho-Chou joined the Kansu braves in fighting the foreigners.[25]

The Islamic troops were organized into eight battalions of infantry, two squadrons of cavalry, two brigades of artillery, and one company of engineers.[26] The Muslim troops reportedly intimidated the Western forces.[27] The Muslims were reportedly eager to join the Boxers and attack the foreigners.[28] They killed a westerner outside Yungting gate.[29] At Zhengyang gate, Muslim troops engaged in combat against British forces.[30][31][32][33]

On June 18, Dong Fuxiang's troops stationed at Hunting park in southern Beijing, attacked Lang Fang. The forces included cavalry at 5,000 men, armed with the latest magazine rifles.[34]

Summary of battles of General Dong Fuxiang:Ts'ai Ts'un battle, July 24, Ho Hsi Wu battle, July 25: An P'ing battle, July 26: Chinese army at Ma T'ou, July 27.[35]

6,000 of the muslim troops under Dong Fuxiang and 20,000 boxers repulsed a relief column, driving them to Huang Ts'un.[36] The muslims camped outside the temples of Heaven and Agriculture.[37]

The Muslim Kansu braves escorted the imperial family to Xi'an when they decided to flee. One of the officers, Ma Fuxiang, was rewarded by the Emperor, being appointed governor of Altay for his service. His brother, Ma Fulu and 4 of his cousins died in combat during the attack on the legations.[38] Ma Fuxing also served under Ma Fulu to guard the Qing Imperial court during the fighting.[39]

Moderates at the Qing court tried to appease the foreigners by moving the Kansu braves out of their way.[40] This proved to be a fatal mistake, as the foreign troops went on an orgy of killing, raping, and looting of innocent civilians. Some had reckoned that the Kansu braves were a tower of defense for China, and would be able to repulse any amount of foreigners.[41]

The imperial government refused to punish General Dong when the foreigners demanded his execution.[42][43]

Upon General Dong's death in 1908, all honors which had been stripped from him were restored and he was given a full military burial.

Manchu Bannermen

Several Manchu princes such as Prince Ching declined to join the boxers and the rest of the imperial army to attack the legations, and even ordered their own Manchu Bannermen to attack the Boxers and the Muslim Kansu braves.[44]

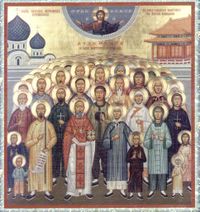

Massacre of missionaries and Chinese Christians

The Taiyuan Massacre was the mass killing of foreign Christian missionaries and of local church members, including children, from July 1900. Two hundred and twenty two Chinese Eastern Orthodox Christians were also killed, along with 182 Protestant missionaries and 500 Chinese Protestants known as the China Martyrs of 1900. Also, 48 Catholic missionaries and 18,000 Chinese Catholics were killed. The Kansu braves under General Dong Fuxiang joined the Boxers in targeting Chinese Christians, going house to house to check the people's religious beliefs. The Kansu braves targeted Christians only, sparing Chinese who had altars to Chinese gods.[45]

The Missionary Herald normally published letters and telegrams sent by priests and their families in Manchu Qing dynasty, in Shanxi province, Taiyuan city. In December 1900, after incrementally more ominous monthly reports, the Missionary Herald broke five-month-old news to its readers: "the entire mission staff in the Province of Shanxi has perished". At the end of June 1900 priests and their families had been lured out of hiding and cast into prison, then executed by the Manchu officials. The Taiyuan missionaries fled into a co-worker's house because Boxers were burning churches and houses, killing Christians and foreigners. Three days later the governor sent four deputies with soldiers, "promising to escort them in safety to the coast". Brought instead to a house near the governor’s residence, they were then "taken to the open space in front of the Governor’s residence, and stripped to the waist, as usual with those beheaded".[46]

| “ | By June 1900 placards calling for the death of foreigners and Christians covered the walls around Beijing. Armed bands combed the streets of the city, setting fire to homes and "with imperial blessing" killing Chinese Christians and foreigners. --Father Geoffrey Korz, of the Orthodox church[47] | ” |

In 2005 British Professor Henry Hart released a book, Lost in the Gobi Desert, to commemorate his great-grandfather's efforts to save the life of western missionaries and their Chinese followers from the hands of the Boxer rebels.

| “ | Boxers blamed “foreign devils” like my great-grandparents for causing northern China's drought and famine, exacerbating economic hardships by building railroads and telegraph lines (because such modern conveniences eliminated jobs), undermining the native textile industry with European imports, infecting and killing Chinese children with Christian prayers and for various other real and imagined infamies. | ” |

| “ | The barbaric Boxer Rebellion came as a sudden thunderstorm; all foreigners were to be killed not in the sudden merciful death of a bullet but sliced to death by big, old rusty knives and swords.... I had an old Winchester rifle and plenty of ammunition ready for the journey....The Boxer uprising ultimately claimed the lives of more than 32,000 Chinese Christians and several hundred foreign missionaries (historian Nat Brandt called it “the greatest single tragedy in the history of Christian evangelicalism”[48] | ” |

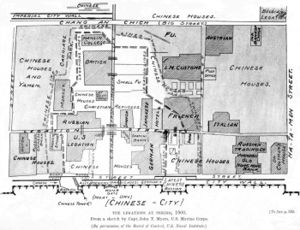

Boxer siege of Beijing

The compound in Beijing remained under siege from Boxer forces from 20 June - 14 August. A total of 473 foreign civilians, 409 soldiers from eight countries, and about 3,000 Chinese Christians took refuge in the Legation Quarter.[49] Under the command of the British minister to China, Claude Maxwell MacDonald, the legation staff and security personnel defended the compound with one old muzzle-loaded cannon; it was nicknamed the International Gun because the barrel was British, the carriage was Italian, the shells were Russian and the crew was American.

During the defence of the legations, a small Japanese force of one officer and 24 sailors commanded by Colonel Shiba, distinguished itself in several ways. Of particular note was that it had the almost unique distinction of suffering greater than 100 percent casualties. This was possible because a great many of the Japanese troops were wounded, entered into the casualty lists, then returned to the line of battle only to be wounded once more and again entered in the casualty lists.[50]

Also under siege in Peking was the North Cathedral, the Beidang, of the Catholic Church. The Beidang was defended by 43 French and Italian soldiers, 33 Catholic Priests and nuns, and about 3,200 Chinese Catholics. The defenders suffered heavy casualties especially from lack of food and Chinese mines exploded in tunnels dug beneath the compound.[51]

Foreign media described the fighting going on in Beijing, as well as the alleged torture and murder of captured foreigners. While it is true that thousands of Chinese Christians were massacred in north China, many horrible stories that appeared in world newspapers were based on the actual murder of men, women and children within the foreign legation. Nonetheless a wave of anti-Chinese sentiment arose in Europe, the United States and Japan.[52] The poorly-armed Boxer rebels were unable to break into the compound, which was relieved by an international army of the Eight-Nation Alliance in August.

Torching of Chinese dwellings

On 23 June 1900 the Boxer rebels started setting fire to an area south of the British Legation, using it as a "frightening tactic" to attack the defenders. And Hanlin Yuan, a complex of courtyards and buildings that housed "the quintessence of Chinese scholarship ... the oldest and richest library in the world", (Yongle Dadian) was just nearby.[53] Sir Claude MacDonald, the commander-in-chief, had become worried that the Boxer rebels might try to burn the Hanlin Yuan, the "buildings at some point being only an arm's length from the British building walls."

On 24 June 1900, when the winds shifted, the unanticipated happened: Hanlin Yuan's group of buildings had caught fire, and the fire was beginning to spread further. Eyewitness' accounts:

- "The old buildings burned like tinder with a roar which drowned the steady rattle of musketry as Tung Fu-shiang's Moslems fired wildly through the smoke from upper windows."

- "Some of the incendiaries were shot down, but the buildings were an inferno and the old trees standing round them blazed like torches."

- "An attempt was made to save the famous Yang Lo Ta Tien [now spelled Yongle Dadian], but heaps of volumes had been destroyed, so the attempt was given up." -eyewitness, Lancelot Giles, son of Herbert A. Giles.

The Manchu authority blamed the British for setting the fire as a defensive measure, whereas the British pointed to the direction of the wind, and claimed that it was either the Boxer rebels or the ordinary Manchu soldiers who "set fire to the Hanlin, working systematically from one courtyard to the next."[54] Rescued from among the burning buildings were portions of the Yongle Encyclopedia, and other works.[55]

Arrival of reinforcements

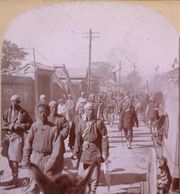

Foreign navies started building up their presence along the northern China coast from the end of April 1900. On 31 May, before the sieges had started and upon the request of foreign embassies in Beijing, an international force of 435 navy troops from eight countries were dispatched by train from Takou to the capital (75 French, 75 Russian, 75 British, 60 U.S., 50 German, 40 Italian, 30 Japanese, 30 Austrian); these troops joined the legations and were able to contribute to their defense. The rebellion was ultimately quashed by the Eight-Nation Alliance of Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States.

First intervention

As the situation worsened a second international force of 2,000 Marines under the command of the British Vice-Admiral Edward Seymour, the largest contingent being British, was dispatched from Takou to Beijing on 10 June. The troops were transported by train from Takou to Tianjin with the agreement of the Chinese government, but the railway between Tianjin and Beijing had been severed. Seymour resolved to move forward and repair the rail or such as the train, or progress on foot as necessary, keeping in mind that the distance between Tianjin and Beijing was only 120 km.

After Tianjin the convoy was surrounded, the railway behind and in front of them was destroyed, and they were attacked from all parts by Chinese irregulars and even Chinese governmental troops. News arrived on 18 June regarding attacks on foreign legations. Seymour decided to continue advancing, this time along the Pei-Ho river, toward Tong-Tcheou, 25 km from Beijing. By the 19th, they had to abandon their efforts due to progressively stiffening resistance and started to retreat southward along the river with over 200 wounded. Commandeering four civilian Chinese junks along the river, they loaded all their wounded and remaining supplies onto them and pulled them along with ropes from the riverbanks. By this point they were very low on food, ammunition and medical supplies. Luckily, they then happened upon The Great Hsi-Ku Arsenal, a hidden Qing munitions cache that the Western Powers had no knowledge of until then. They immediately captured and occupied it, discovering not only German Krupp-made field guns, but rifles with millions of rounds in ammunition, along with millions of pounds of rice and ample medical supplies.

| Forces of the Eight-Nation Alliance (1900 Boxer Rebellion)  Left to right: Britain, United States, Russia, British India, Germany, France, Austria, Italy, Japan. |

|||

| Countries | Warships (units) |

Marines (men) |

Army (men) |

| Japan | 18 | 540 | 20,300 |

| Russia | 10 | 750 | 12,400 |

| United Kingdom | 8 | 2,020 | 10,000 |

| France | 5 | 390 | 3,130 |

| United States | 2 | 295 | 3,125 |

| Germany | 5 | 600 | 300 |

| Italy | 2 | 80 | |

| Austria–Hungary | 1 | 75 | |

| Total | 51 | 4,750 | 49,255 |

There they dug in and awaited rescue. A Chinese servant was able to infiltrate through the Boxer and Qing lines, informing the Eight Powers of their predicament. Surrounded and attacked nearly around the clock by Qing troops and Boxers, they were at the point of being overrun. On 25 June a regiment composed of 1800 men, (900 Russian troops from Port-Arthur, 500 British seamen, with an ad hoc mix of other assorted western troops) finally arrived. Spiking the mounted field guns and setting fire to any munitions that they could not take (an estimated £3 million worth), they departed the Hsi-Ku Arsenal in the early morning of 26 June, with the loss of 62 killed and 228 wounded.[56]

Second intervention

With a difficult military situation in Tianjin and a total breakdown of communications between Tianjin and Beijing, the allied nations took steps to reinforce their military presence significantly. On 17 June they took the Taku Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and from there brought increasing numbers of troops on shore.

The international force with British Lieutenant-General Alfred Gaselee acting as the commanding officer of the Eight-Nation Alliance, eventually numbered 55,000, with the main contingent being composed of Japanese soldiers: Japanese (20,840), Russian (13,150), British (12,020), French (3,520), U.S.(3,420), German (900), Italian (80), Austro-Hungarian (75) and anti-Boxer Chinese troops.[57] The international force finally captured Tianjin on 14 July under the command of the Japanese Colonel Kuriya, after one day of fighting.

Notable exploits during the campaign were the seizure of the Taku Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and the boarding and capture of four Chinese destroyers by Roger Keyes. Among the foreigners besieged in Tianjin was a young American mining engineer named Herbert Hoover.[58]

The march from Tianjin to Beijing of about 120 km consisted of about 20,000 allied troops. On 4 August there were approximately 70,000 Imperial troops with anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000 Boxers along the way. They only encountered minor resistance and the battle was engaged in Yangcun, about 30 km outside Tianjin, where the 14th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. and British troops led the assault. The weather was a major obstacle, extremely humid with temperatures sometimes reaching 110 °F (43 °C).

The international force reached and occupied Beijing on 14 August. All the nationalities in the international force raced to be the first to liberate the besieged Legation Quarter with the British winning the race. The U.S. was able to play a minor role, in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion due to the presence of U.S. ships and troops deployed in the Philippines since the U.S. conquest of the Spanish American and Philippine-American War. In the U.S. military the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion was known as the China Relief Expedition. American soldiers scaling the walls of Beijing is one of the most iconic images of the Boxer Rebellion.[59]

"An Orgy of Looting"

The intermediate aftermath of the siege in Beijing was "an orgy of looting" by soldiers, civilians, and missionaries. Each nationality in the expeditionary force accused the other of being the worst looters—and all were guilty. Beijing was a treasure house of silks, porcelain, furs, jewelry, bronzes, and silver and the foreigners ransacked the city for everything of value. An American diplomat, Herbert Squires, filled several railroad cars with loot. The British Legation held loot auctions every afternoon and proclaimed, "looting on the part of British troops was carried out in the most orderly manner." The Catholic North Cathedral was a storehouse and super market for purchasing loot. The American commander General Adna Chaffee banned looting by American soldiers, but the ban was ineffectual.[60]

The missionaries were the most condemned—although not any more guilty than most foreigners—of looting. Mark Twain reflected American outrage against looting and imperialism in his essay, "To the Person Sitting in Darkness". American Board Missionary William Scott Ament was his target.[61] To provide restitution to missionaries and Chinese Christian families whose property had been destroyed, Ament guided American troops through villages to punish Boxers and confiscate their property. When Mark Twain read of this expedition, he wrote a scathing attack on the "Reverend bandits of the American Board."[62] Ament was one of the most respected and courageous missionaries in China and the controversy between him and Mark Twain was front page news during much of 1901. Ament's counterpart on the distaff side was doughty British missionary Georgina Smith who presided over a neighborhood in Beijing as judge and jury.[63]

Occupation

Beijing, Tianjin, and other cities in northern China were occupied for more than one year by the international expeditionary force under the command of German General Alfred Graf von Waldersee. The German force arrived too late to take part in the fighting, but undertook several punitive expeditions to the countryside against the Boxers. Although atrocities by foreign troops were common, German troops in particular were criticized for their enthusiasm in carrying out Kaiser Wilhelm II’s words. On 27 July 1900 when Wilhelm II spoke during departure ceremonies for the German contingent to the relief force in China, an impromptu, but intemperate reference to the Hun invaders of continental Europe would later be resurrected by British propaganda to mock Germany during World War I and World War II.

"Just as the Huns a thousand years ago, under the leadership of Attila, gained a reputation by virtue of which they still live in historical tradition, so may the name Germany become known in such a manner in China, that no Chinese will ever again dare to look askance at a German."[64]

The Germans were not the only offenders. On behalf of Chinese Catholics, French troops ravaged the countryside around Beijing to collect indemnities—and on one occasion arresting Ament who, a one-man army, beat them to the punch in gathering wealth from some villages. Nor were the soldiers of other nationalities any better behaved. "The Russian soldiers are ravishing the women and committing horrible atrocities" in the sector of Beijing they occupied. The Japanese were noted for their skill in beheading Boxers or people suspected of being Boxers. General Chaffee commented, "It is safe to say that where one real Boxer has been killed ...fifty harmless coolies or laborers on the farms, including not a few women and children, have been slain."[65]

War reparations

On 7 September 1901, the Qing court was compelled to sign the "Boxer Protocol" also known as Peace Agreement between the Eight-Nation Alliance and China. The protocol ordered the execution of 10 high-ranking officials linked to the outbreak and other officials who were found guilty for the slaughter of Westerners in China.

China was fined war reparations of 450,000,000 tael of fine silver (1 tael = 1.2 troy ounces) for the loss that it caused. The reparation would be paid within 39 years, and would be 982,238,150 taels with interests (4 percent per year) included. To help meet the payment it was agreed to increase the existing tariff from an actual 3.18 percent to 5 percent, and to tax hitherto duty-free merchandise. The sum of reparation was estimated by the Chinese population (roughly 450 million in 1900), to let each Chinese pay one tael. Chinese custom income and salt tax were enlisted as guarantee of the reparation. Russia got 30 percent of the reparation, Germany 20 percent, France 15.75 percent, Britain 11.25 percent, Japan 7.7 percent and the US share was 7 percent.[66]

China paid 668,661,220 taels of silver from 1901 to 1939, equivalent in 2010 to $61,518,619,705 on a purchasing power parity basis (see Tael). The British signatory of the Protocol was Sir Ernest Satow.

A large portion of the reparations paid to the United States was diverted to pay for the education of Chinese students in U.S. universities under the Boxer Rebellion Indemnity Scholarship Program. To prepare the students chosen for this program an institute was established to teach the English language and to serve as a preparatory school for the course of study chosen. When the first of these students returned to China they undertook the teaching of subsequent students; from this institute was born Tsinghua University. Some of the reparation due to Britain was later earmarked for a similar program.

The China, or Inland Mission, lost more members than any other missionary agency:[67] 58 adults and 21 children were killed. However, in 1901, when the allied nations were demanding compensation from the Chinese government, Hudson Taylor refused to accept payment for loss of property or life in order to demonstrate the meekness of Christ to the Chinese.[68]

Long-term results

The great powers stopped short of finally colonizing China. From the Boxer rebellions, they learned that the best way to govern China was through the Chinese dynasty, instead of direct dealing with the Chinese people (as a saying “The people are afraid of officials, the officials are afraid of foreigners, and the foreigners are afraid of the people" (老百姓怕官,官怕洋鬼子,洋鬼子怕老百姓)). Dowager Cixi used Boxers to fight foreigners largely because foreigners sympathized with the Guangxu Emperor, who had been on house arrest after an aborted reformation. Eventually, as an unwritten agreement, Dowager Cixi was allowed to stay in power, since comparatively, Cixi could use her influence to suppress the Chinese anti-western sentiment better than the weak and ineffectual Guangxu Emperor. The Guangxu Emperor spent the rest of his life in house arrest.

In October 1900 Russia was busy occupying much of the northeastern province of Manchuria, a move which threatened Anglo-American hopes of maintaining what remained of China's territorial integrity and an openness to commerce under the Open Door Policy. This behavior led ultimately to the Russo-Japanese War, where Russia was defeated at the hands of an increasingly confident Japan.

Among the Imperial powers, Japan gained prestige due to its military aid in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion and was now seen as a power. Its clash with Russia over Liaodong and other provinces in eastern Manchuria, long considered by the Japanese as part of their sphere of influence, led to the Russo-Japanese War when two years of negotiations broke down in February 1904. Germany earned itself the derogatory moniker "Hun" at the beginning of World War I when intrepid propagandists resurrected Wilhelm II’s 1900 speech. The Russian Lease of the Liaodong (1898) was confirmed.

Besides the compensation, Empress Dowager Cixi reluctantly started some reformations despite her previous view. The imperial examination system for government service was eliminated; as a result, the classical system of education was replaced with a European liberal system that led to a university degree. After the death of Empress Dowager Cixi and the Guangxu Emperor (on the same day, mysteriously) in 1908, the regent (Guangxu Emperor's brother) launched reformation. However, these efforts seemed to be too late. The revolutionaries within Han Chinese could not wait. The imperial government's humiliating failure to defend China against the foreign powers contributed to the growth of nationalist resentment against the "foreigner" Qing dynasty (who were descendants of the Manchu conquerors of China). By circumstance, the Qing Dynasty, weakened by the war and the 1911 revolution, led by Sun Yat-sen, became the last dynasty in Chinese history.

The effect on China was a weakening of the dynasty as well as a weakened national defense. The structure was temporarily sustained by the Europeans. Behind the international conflict, it further internally deepened the ideological differences between northern-Chinese anti-foreign royalists and southern-Chinese anti-Qing revolutionists. This scenario in the last Chinese empire gradually escalated to a chaotic warlord era in which the most powerful northern warlords were hostile towards the first Chinese republic in the south until the 1930s when the Chinese communists and Japanese imperialists became the greatest threats to the republic and the northern warlords respectively. Before the ultimate defeat of the Boxer Rebellion, all anti-Qing movements in the previous century such as the Taiping Rebellion were successfully suppressed by the Qing and her foreign collaborators.

Conflicting depictions of Boxers

Views differ as to whether the Boxers are better seen as anti-imperialist or as futile opponents of inevitable change. In the People's Republic of China, orthodox textbooks used to analyze the Boxer movement as an anti-imperialist, patriotic peasant movement whose failure was due to the lack of leadership from the modern working class. In recent decades, however, large-scale projects of village interviews and explorations of archival sources have led historians to take a more nuanced view. Some Western scholars, such as Joseph Esherick, have seen the movement as anti-imperialist; while others view this interpretation as anachronistic in that the Chinese nation had not been formed and the Boxers were more concerned with regional issues. Esherick comments that "confusion about the Boxer Uprising is not simply a matter of popular misconceptions," for "there is no major incident in China's modern history on which the range of professional interpretation is so great.".[69] Paul Cohen's recent history includes a survey of "the Boxers as myth," showing how their memory was used in changing ways in 20th-century China from the New Culture Movement to the Cultural Revolution.[70]

In 2006 Yuan Weishi, a professor of philosophy at Zhongshan University in Guangzhou, China, published an essay titled Modernisation and History Textbooks, criticizing the official theme of government-issued middle schools history textbooks, claiming that they contain numbers of non-neutral historical interpretations. Yuan wrote that these "criminal actions brought unspeakable suffering to the nation and its people! These are all facts that everybody knows, and it is a national shame that the Chinese people cannot forget."[71] For many years, history text books had been lacking in neutrality in presenting the Boxer Rebellion as a "magnificent feat of patriotism", and not presenting the view that the majority of the Boxer rebels were both violent and xenophobic. Professor Yuan stated that Manchu rulers did not comply with signed international treaties, and that it is wrong to blame "the Opium Wars of the mid-1800s entirely on foreign nations".[72] On the other hand, such views are criticized and considered to be unfair, unneutral and logically absurd by some people and Yuan Weishi is even called Hanjian (漢奸, betrayer of the Han)[73] by some Chinese people, which at first glance appears ironic considering that he based his views on Han nationalism.

The philosopher Tang Junyi viewed the Boxer Uprising as a religious war between the Chinese and Christianity.[74] In fact, facing what they viewed as an aggressive religious invasion by Christianity, Chinese Righteous Harmony Society had the slogan "Defend Chinese Religion (保華教, or 保漢教) and Get Rid of Foreign Religion (of Christianity) (滅洋教)." Some scholars consider it to be a war against the invasion of China by the foreign religion of Christianity.

In fiction

- The 1963 film 55 Days at Peking was a dramatization of the Boxer rebellion. Shot in Spain, it needed thousands of Chinese extras, and the company sent scouts throughout Spain to hire as many as they could find.[75]

- In 1975 Hong Kong's Shaw Brothers studio produced the film Boxer Rebellion (八國聯軍, Pa kuo lien chun) under director Chang Cheh with one of the highest budgets to tell a sweeping story of disillusionment and revenge.[76] It depicted followers of the Boxer clan being duped into believing they were impervious to attacks by firearms. The film starred Alexander Fu Sheng, Chi Kuan Chun, Wang Lung-Wei and Richard Harrison.

- The novel Moment In Peking, by Lin Yutang, opens during the Boxer Rebellion, and provides a child's-eye view of the turmoil through the eyes of the protagonist.

- The novel The Palace of Heavenly Pleasure, by Adam Williams, describes the experiences of a small group of western missionaries, traders and railway engineers in a fictional town in northern China shortly before and during the Boxer Rebellion.

- Parts I and II of C. Y. Lee's China Saga (1987) involve events leading up to and during the Boxer Rebellion, revolving around a character named Fong Tai.

- The horror play La Dernière torture (The Ultimate Torture), written by André de Lorde and Eugène Morel in 1904 for the Grand Guignol theater (just four years following the events depicted), is set during the Boxer Rebellion, in the French area of the fortified legation compound, specifically on 22 July 1900, the 32nd day of the Boxers' siege of the compound.

- The Last Empress, by Anchee Min, describes the long reign of the Empress Dowager Cixi in which the siege of the legations is one of the climactic events in the novel.

- The Douglas Reeman novel The First to Land, part of the Blackwood saga, depicts an officer of Royal Marines during the siege of Peking.

- The novel Fenwick Travers and the Years of Empire, by Raymond M. Saunders, depicts American antihero Fenwick Travers taking an active role in the Boxer rebellion.

- China Under the Empress Dowager by Bland and Backhouse, 1911, including The Diary of His Excellency Ching Shan: Being a Chinese Account of the Boxer Rebellion.

- In the Buffy the Vampire Slayer episode "Fool for Love" (2001) Spike recounts his killing of a Slayer at the Boxer Rebellion, and the following Angel episode "Darla" shows the same events from Angel's point of view.

- The 2003 movie, Shanghai Knights, staring Jackie Chan and Owen Wilson, shows that the Boxers still exist, working for Lord Rathbone, who wants to assassinate many members of the British Royal Family.

- The Diamond Age or, A Young Lady's Illustrated Primer, by Neal Stephenson, includes a quasi-historical re-telling of the Boxer Rebellion as an integral component of the novel.

- The 2007 Peter Watt Novel The Stone Dragon, tells the story of a Chinese-Australian importation magnate who travels to Peking to attempt to rescue his daughter, who has been taken captive by the Boxer rebels.

- The Rebellion is mentioned in the Herge Tintin story "The Blue Lotus" by Tintin's Chinese friend Chang Chong-Chen when they first meet after Tintin saves the boy from drowning. It is a pivotal and poignant moment relating to the views Chinese and European people had of each other at the time. The boy asks Tintin why he saved him from drowning as, according to Chang's uncle who fought in the Rebellion, all white people were wicked. Chang mispronounces it however, calling it 'the battle of Righteous and Harmonious Fists.'

- Besieged!, a play written by Iowa's Kirkwood Community College staff member, Pamela Edwards, was performed by the theatre department in 2010. It covers President and Mrs. Herbert Hoover's early years of marriage spent in China during the Boxer Rebellion.

- In the Dad's Army episode Museum Piece Jones and Walker find a rocket-artillery launcher used against the Boxers (to which Jones replies "the poor creatures!"). Back at the Church Hall Jones and Walker show the weapon to the rest of the Platoon but Mainwaring says they'll take it back to the museum as it's too antiquated, claiming something like "warfare has progressed a bit since the rocket".

- A falsified diary, Diary of his Excellency Ching-Shan: Being a Chinese Account of the Boxer Troubles, including text written by Edmund Backhouse, who said he recovered the document from a burnt building. It is suspected that Backhouse falsified the document, as well as other stories, because he was prone to tell tales dubious in nature, including claims of nightly visits to the Empress Cixi.

In art

The rebellion was covered in the western illustrated press by artists and photographers. Paintings and prints were also published including Japanese wood-blocks.[77]

See also

- Battle of Peking

- China Relief Expedition Campaigns

- Opium wars

- Righteous Harmony Society

- US Army 6th Cavalry Regiment (United States)

- US Army 14th Infantry Regiment (United States) "Golden Dragons"

- US Army 15th Infantry Regiment (United States)

- US Army China Campaign Medal

- US Navy China Relief Expedition Medal

References

- ↑ Esherick, 154

- ↑ Spence, In Search of Modern China, pp. 230-235; Keith Schoppa, Revolution and Its Past, pp. 118-123.

- ↑ G. William Skinner divided China into eight "macroregions": "North China [located along the coast], Northwest China [inland, west of North China], the Lower, Middle and Upper Yangzi [all three ranging, in succession, from the coast to the western border], the Southeast Coast, Lingnan (centered on Canton) and the Southwestern region around Yunnan and Guizhou" (Esherick 1987, 3-4)

- ↑ Spence (1999) pp. 231-232.

- ↑ Thompson, Larry Clinton. William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: Heroism, Hubris, and the Ideal Missionary. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009, 7-8

- ↑ Thompson, 9

- ↑ Thompson, 11-12

- ↑ "Imperialism, for Christ's Sake," Ch. 3 , Esherick, The Origins of the Boxer Uprising, pp. 68-95.

- ↑ Thompson, 12

- ↑ Countrydstudies.us

- ↑ Thecorner.org

- ↑ Thompson, 40-53

- ↑ "The Gathering Storm," Ch 7, "Prairie Fire," Ch 10 Esherick, pp. 167-205, 271-313.

- ↑ Jonathan Neaman Lipman (2004). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 181. ISBN 0295976446. http://books.google.com/?id=90CN0vtxdY0C&pg=PA169&dq=ma+fuxiang+boxer&cd=1#v=snippet&q=gansu%20muslim%20troops%20had%20been%20the%20most%20steadfast. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Lynn E. Bodin (1979). The Boxer Rebellion. Osprey Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 0850453356. http://books.google.com/?id=2YleP1OP4HsC&pg=PA26&dq=kansu+braves+rabble&cd=1#v=onepage&q=kansu%20braves%20rabble. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ B. L. Putnam Weale (2006). Indiscreet Letters from Peking. Echo Library. p. 10. ISBN 1406834211. http://books.google.com/?id=aaA8ht_sDZwC&pg=PA10&dq=kansu+braves+r&cd=3#v=onepage&q=mohammedan%20braves. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Ronald Acott Hall (1966). Eminent authorities on China. Chʼeng Wen. p. 31, 38, 139. http://books.google.com/?id=zUxUAAAAMAAJ&cd=1&dq=kansu+braves+r&q=braves. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Chester M. Biggs (2003). The United States marines in North China, 1894-1942. McFarland. p. 25. ISBN 078641488X. http://books.google.com/?id=S8YtE0SIDq0C&pg=PA25&dq=marines+kansu+braves&cd=1#v=onepage&q=marines%20kansu%20braves. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Max Boot (2003). The savage wars of peace: small wars and the rise of American power. Da Capo Press. p. 82. ISBN 046500721X. http://books.google.com/?id=0lIg-lGwqBoC&pg=PA82&dq=marines+kansu+braves&cd=2#v=onepage&q=marines%20kansu%20braves. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Kansu Soldiers (Tung Fu Hsiang's)

- ↑ Kansu Braves

- ↑ Clark, Kenneth G.. "The Boxer Uprising 1899 - 1900.". http://www.russojapanesewar.com/boxers.html. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Ching-shan, Jan Julius Lodewijk Duyvendak (1976). The diary of His Excellency Ching-shan: being a Chinese account of the Boxer troubles. University Publications of America. p. 14. ISBN 0890930740. http://books.google.com/?id=6WsKAQAAIAAJ&cd=19&dq=kansu+braves&q=killed+a+foreign. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Upton Close (1924). In the land of the laughing Buddha: the adventures of an American barbarian in China. G. P. Putnam's sons. p. 267. http://books.google.com/books?id=IJACAAAAMAAJ&q=skin+and+ate+the+heart+of+german+von+ketteler&dq=skin+and+ate+the+heart+of+german+von+ketteler&hl=en&ei=0PlVTITQBoH98AbM5u3LBA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAQ. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ M. Th. Houtsma, A. J. Wensinck (1993). E. J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. Stanford: Brill Publishers. p. 850. ISBN 9004097961. http://books.google.com/?id=rezD7rvuf9YC&pg=PA850&lpg=PA850&dq=ma+fu-hsiang&q=ma%20fu-hsiang. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Peter Harrington, Michael Perry (2001). Peking 1900: the Boxer rebellion. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 1841761818. http://books.google.com/?id=xxE6rybpvHQC&pg=PA25&dq=kansu+braves&cd=1#v=onepage&q=kansu%20braves. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Sterling Seagrave, Peggy Seagrave (1993). Dragon lady: the life and legend of the last empress of China. Vintage Books. p. 318. ISBN 0679733698. http://books.google.com/?id=J07_tPJu9M8C&q=kansu+braves&dq=kansu+braves&cd=10. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Philip Walsingham Sergeant (1910). The great empress dowager of China. England: Hutchinson & co.. p. 231. http://books.google.com/?id=2XpCAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA231&dq=marines+kansu+braves&cd=7#v=onepage&q=marines%20kansu%20braves. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Ching-shan, Jan Julius Lodewijk Duyvendak (1976). The diary of His Excellency Ching-shan: being a Chinese account of the Boxer troubles. University Publications of America. p. 14. ISBN 0890930740. http://books.google.com/?id=6WsKAQAAIAAJ&cd=19&dq=kansu+braves&q=killed+a+foreign. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 72. ISBN 0700710264. http://books.google.com/?id=hUEswLE4SWUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=ma+fuxiang+boxer&q=hui%20troops%20zhengyang. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Lynn E. Bodin (1970). The Boxer Rebellion. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 0850453356. http://books.google.com/?id=2YleP1OP4HsC&pg=PA24-IA3&dq=kansu+braves+boxer&cd=6#v=snippet&q=imperial%20chinese%20infantryman%20kansu%20braves%20boxer%20manchu. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Picture of Muslim soldier

- ↑ picture of general dong fuxiang

- ↑ Arthur Henderson Smith (1901). China in convulsion, Volume 2. F. H. Revell Co.. p. 441. http://books.google.com/?id=WmAuAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA452-IA1&dq=tung+fu-hsiang+japanese+bodyguard&q=tung%20fu%20hsiang%20regular%20troops%20rifles. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Arthur Henderson Smith (1901). China in convulsion, Volume 2. F. H. Revell Co.. p. 393. http://books.google.com/?id=WmAuAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA393&lpg=PA393&dq=tung+fu-hsiang+japanese+bodyguard&q=tung%20fu%20hsiang%20battle. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ William Meyrick Hewlett (1900). Diary of the siege of the Peking legations, June to August, 1900. Pub. for the editors of the "Harrovian," by F. W. Provost. p. 10. http://books.google.com/?id=3gQWAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA10&dq=tung+fu-hsiang+sir+shots&q=tung%20fu-hsiang%20sir%20shots. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Bertram L. Simpson (2001). Indiscreet Letters from Peking: Being the Notes of an Eye-witness. Adegi Graphics LLC. p. 22. ISBN 1402194889. http://books.google.com/?id=0Yu9Tf5leGgC&pg=PA22&dq=kansu+braves+tea+tung&q=kansu%20braves%20tea%20tung. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Jonathan Neaman Lipman (2004). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 169. ISBN 0295976446. http://books.google.com/?id=90CN0vtxdY0C&pg=PA169&dq=ma+fuxiang+ma+fuxiang+gansu+braves+imperial+xi'an&q=ma%20fuxiang%20ma%20fuxiang%20gansu%20braves%20imperial%20xi'an. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Garnaut, Anthony. "From Yunnan to Xinjiang:Governor Yang Zengxin and his Dungan Generals". Pacific and Asian History, Australian National University). http://www.ouigour.fr/recherches_et_analyses/Garnautpage_93.pdf. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- ↑ Sterling Seagrave, Peggy Seagrave (1993). Dragon lady: the life and legend of the last empress of China. Vintage Books. p. 311. ISBN 0679733698. http://books.google.com/?id=J07_tPJu9M8C&dq=kansu+braves+from+the+marines+path&q=path+braves+court. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Sterling Making of America Project (1914). The Atlantic monthly, Volume 113 By Making of America Project. Atlantic Monthly Co.. p. 80. http://books.google.com/?id=rcdkmohiuuQC&pg=PA80&dq=removing+the+kansu+brave&q=tower%20of%20defense. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Public opinion, Volume 29. Public Opinion Co.. 1900. p. 636. http://books.google.com/?id=w9oaAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA636&dq=tung+fu-hsiang+sir+shots&q=general%20tung%20punishment%20emperor%20kwang. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Jonathan Neaman Lipman (2004). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 181. ISBN 0295976446. http://books.google.com/?id=90CN0vtxdY0C&pg=PA224&dq=dong+fuxiang+doing+his+job&q=dong%20fuxiang%20did%20not%20want%20to%20punish. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Appletons' annual cyclopædia and register of important events of the year ..., Volume 5. D. Appleton & Co.. 1901. p. 112. http://books.google.com/?id=uqcoAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA112&dq=manchu+princes+kansu+braves+boxers&q=manchu%20princes%20kansu%20braves%20boxers. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Sterling Making of America Project (1914). The Atlantic monthly, Volume 113 By Making of America Project. Atlantic Monthly Co.. p. 80. http://books.google.com/?id=rcdkmohiuuQC&pg=PA80&dq=kansu+braves&cd=2#v=onepage&q=kansu%20braves. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "The Boxer Rebellion". bms world mission. http://www.bmsworldmission.org/standard.aspx?id=9436. Retrieved 14 Oct. 2008.

- ↑ Korz, Father Geoffrey. "The Chinese Martyrs of the Boxer Rebellion". All Saints of North America Orthodox church. http://www.orthodox.cn/saints/korz_en.htm. Retrieved 21 Oct. 2008.

- ↑ Hart, Henry (3 January 2005). "Lost in the Gobi Desert Hart retraces great-grandfather’s footsteps". W&M News (College of William & Mary). http://web.wm.edu/news/archive/index.php?id=4174. Retrieved 21 Oct. 2008.

- ↑ Thompson, 84-85

- ↑ Fleming, 1959. pp. 143-144.

- ↑ Thompson, 85, 170-171

- ↑ Elliott (1996)

- ↑ "Destruction Of Chinese Books In The Peking Siege Of 1900. Donald G. Davis, Jr. University of Texas at Austin, USA Cheng Huanwen Zhongshan University, PRC". International Federation of Library Association. http://www.ifla.org/IV/ifla62/62-davd.htm. Retrieved 26 Oct. 2008.

- ↑ "Boxer Rebellion - China 1900". Historik Orders, Ltd.. Archived from the original on 2006=01-09. http://web.archive.org/web/20060109013626/http://www.historikorders.com/chinaboxer.htm. Retrieved 20 Oct. 2008.

- ↑ The Strand Magazine, May 1906, page 600

- ↑ Account of the Seymour column in "The Boxer Rebellion", pgs 100-104, Diane Preston.

- ↑ Russojapanesewarweb

- ↑ Thompson, 96

- ↑ Thompson, 177

- ↑ Thompson, 194-197

- ↑ Thompson, 207-208

- ↑ Fleming, The Siege at Peking, 136

- ↑ Thompson, 200, 204-214

- ↑ Michael Hunt, The Making of a Special Relationship: The United States and China to 1914 (Columbia UP 1986): 286-88

- ↑ Thompson, 199-204

- ↑ Hsu, 481

- ↑ Archive.org

- ↑ Broomhall (1901), several pages

- ↑ Esherick, p, xiv

- ↑ Cohen, History in Three Keys Pt Three, "The Boxers As Myth."

- ↑ "History Textbooks in China". Eastsouthwestnorth. http://www.zonaeuropa.com/20060126_1.htm. Retrieved 23 Oct. 2008.

- ↑ Pan, Philip P. (25 January 2006). "Leading Publication Shut Down In China". Washington Post Foreign Service. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/01/24/AR2006012401003.html. Retrieved 19 Oct. 2008.

- ↑ 网友评论:评中山大学袁时伟的汉奸言论和混蛋逻辑

- ↑ 唐君毅《中國人文精神之發展》,第329-335頁,台灣學生書局,2002年6月

- ↑ 55 Days at Peking at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ HKflix

- ↑ Frederic A. Sharf and Peter Harrington. China 1900: The Artists' Perspective. London: Greenhill, 2000. ISBN 1-85367-409-5.

Bibliography

- Brandt, Nat (1994). Massacre in Shansi. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-0282-0, ISBN 1-58348-347-0 (Pbk).

- Broomhall, Marshall (1901). Martyred Missionaries of The China Inland Mission; With a Record of The Perils and Sufferings of Some Who Escaped. London: Morgan and Scott. http://books.google.com/?id=yVtXfdulqUMC&pg=PR3&dq=broomhall+martyred.

- Chen, Shiwei. "Change and Mobility: the Political Mobilization of the Shanghai Elites in 1900." Papers on Chinese History 1994 3(spr): 95-115.

- Cohen, Paul A. (1997). History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth Columbia University Press. online edition

- Cohen, Paul A. "The Contested Past: the Boxers as History and Myth." Journal of Asian Studies 1992 51(1): 82-113. Issn: 0021-9118

- Elliott, Jane. "Who Seeks the Truth Should Be of No Country: British and American Journalists Report the Boxer Rebellion, June 1900." American Journalism 1996 13(3): 255-285. Issn: 0882-1127

- Esherick, Joseph W. (1987). The Origins of the Boxer Uprising University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06459-3

- Fleming, Peter. The Siege at Peking. New York: Dorset Press. 1990 (originally published 1959). ISBN 0-88029-462-0

- Harrington, Peter. Peking 1900: The Boxer Rebellion. Oxford: Osprey, 2001. ISBN 1-84176-181-8

- Harrison, Henrietta. "Justice on Behalf of Heaven." History Today (2000) 50(9): 44-51. Issn: 0018-2753.

- Jellicoe, George (1993). The Boxer Rebellion, The Fifth Wellington Lecture, University of Southampton, University of Southampton. ISBN 0-85432-516-6.

- Hsu, Immanuel C.Y. (1999). The rise of modern China, 6 ed. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512504-5.

- Hunt, Michael H. "The Forgotten Occupation: Peking, 1900–1901." Pacific Historical Review 48 (4) (November 1979): 501–529.

- Preston, Diana (2000). The Boxer Rebellion. Berkley Books, New York. ISBN 0-425-18084-0. online edition

- Preston, Diana. "The Boxer Rising." Asian Affairs (2000) 31(1): 26-36. ISSN 0306-8374.

- Purcell, Victor (1963). The Boxer Uprising: A background study. online edition

- Sharf, Frederic A., and Peter Harrington (2000). China 1900: The Eyewitnesses Speak. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-410-9.

- Sharf, Frederic A., and Peter Harrington (2000). China 1900: The Artists' Perspective. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-409-5

- Seagrave, Sterling (1992). Dragon Lady: The Life and Legend of the Last Empress of China Vintage Books, New York. ISBN 0-679-73369-8. Challenges the notion that the Empress-Dowager used the Boxers. She is portrayed sympathetically.

- Spence, Johnathon D.. "The Search for Modern China" 2nd ed.. New York: Norton, 1999.

- Tiedemann, R. G. "Boxers, Christians and the Culture of Violence in North China." Journal of Peasant Studies 1998 25(4): 150-160. ISSN 0306-6150.

- Thompson, Larry Clinton. William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: Heroism, Hubris, and the "Ideal Missionary". Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009

- Warner, Marina (1993). The Dragon Empress The Life and Times of Tz'u-his, 1835–1908, Empress Dowager of China. Vintage. ISBN 0-09-916591-0

- Eva Jane Price. China journal, 1889-1900: an American missionary family during the Boxer Rebellion, (1989). ISBN 0-684-19851-8; see Susanna Ashton, "Compound Walls: Eva Jane Price's Letters from a Chinese Mission, 1890-1900." Frontiers 1996 17(3): 80-94. ISSN: 0160-9009.

External links

- September 1900 San Francisco Newspaper

- 55 Days at Peking at the Internet Movie Database

- Pa kuo lien chun at the Internet Movie Database

- University of Washington Library's Digital Collections – Robert Henry Chandless Photographs

- Proceedings of the Tenth Universal Peace Congress, 1901

- Pictures from the Siege of Peking, from the Caldwell Kvaran archives

- Eyewitness account: When the Allies Entered Peking, 1900,an excerpt of Pierre Loti's Les Derniers Jours de Pékin (1902).

Additional source

- (Chinese) 唐德刚:传教?信教?吃教?反教形形色色平议

- (Chinese) 义和团和清廷的大屠杀

- (Chinese) Yuan Weishi:尋求真相:为何、何时、如何「反帝反封建」?

- (Chinese) Yuan Weishi:现代化与历史教科书

- (Chinese) 金滿樓:庚子国乱的反思义和拳到底是什么?

- (Chinese) 重評義和團運動(一)

- (Chinese) 八國聯軍中的美國(一)

- (Chinese) 1900年8月14日 八國聯軍向北京發起總攻

- (Chinese) 清政府在義和團事件中的角色

- (Chinese) s:zh:神助拳 義和團 只因鬼子鬧中原

- (Chinese) s:zh:庚子國變記

- (Chinese) s:zh:拳變餘聞

- (Chinese) s:zh:西巡迴鑾始末

Online video

- (Chinese)袁腾飞----义和团

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||